Public Memory

Here are some notes on how the Cairo zkVM encodes its (public) memory in the AIR (arithmetization) of the STARK.

If you’d rather watch a 25min video of the article, here it is:

The AIR arithmetization is limited on how it can handle public inputs and outputs, as it only offer boundary constraints. These boundary constraints can only be used on a few rows, otherwise they’re expensive to compute for the verifier. (A verifier would have to compute for some given , so we want to keep small.)

For this reason Cairo introduce another way to get the program and its public inputs/outputs in: public memory. This public memory is strongly related to the memory vector of cairo which a program can read and write to.

In this article we’ll talk about both. This is to accompany this video and section 9.7 of the Cairo paper.

Cairo’s memory

Cairo’s memory layout is a single vector that is indexed (each rows/entries is assigned to an address starting from 1) and is segmented. For example, the first rows are reserved for the program itself, some other rows are reserved for the program to write and read cells, etc.

Cairo uses a very natural “constraint-led” approach to memory, by making it write-once instead of read-write. That is, all accesses to the same address should yield the same value. Thus, we will check at some point that for an address and a value , there’ll be some constraint that for any two and such that , then .

Accesses are part of the execution trace

At the beginning of our STARK, we saw in How STARKs work if you don’t care about FRI that the prover encodes, commits, and sends the columns of the execution trace to the verifier.

The memory, or memory accesses rather (as we will see), are columns of the execution trace as well.

The first two columns introduced in the paper are called and . For each rows in these columns, they represent the access made to the address in memory, with value . As said previously, we don’t care if that access is a write or a read as the difference between them are blurred (any read for a specific address could be the write).

These columns can be used as part of the Cairo CPU, but they don’t really prevent the prover from lying about the memory accesses:

- First, we haven’t proven that all accesses to the same addresses always return the same value .

- Second, we haven’t proven that the memory contains fixed values in specific addresses. For example, it should contain the program itself in the first cells.

Let’s tackle the first question first, and we will address the second one later.

Another list to help

In order to prove that the two columns in the part of the execution trace, Cairo adds two columns to the execution trace: and . These two columns contain essentially the same things as the columns, except that these times the accesses are sorted by address.

One might wonder at this point, why can’t L1 memory accesses be sorted? Because these accesses represents the actual memory accesses of the program during runtime, and this row by row (or step by step). The program might read the next instruction in some address, then jump and read the next instruction at some other address, etc. We can’t force the accesses to be sorted at this point.

We will have to prove (later) that and represent the same accesses (up to some permutation we don’t care about).

So let’s assume for now that correctly contains the same accesses as but sorted, what can we check on ?

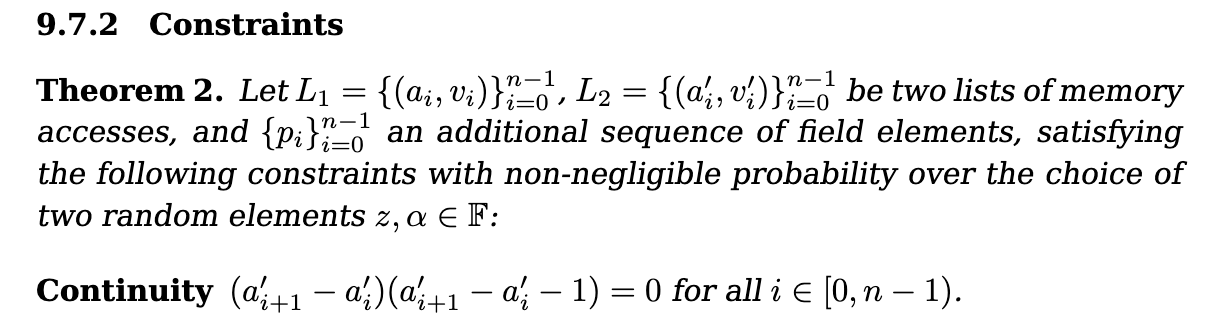

The first thing we want to check is that it is indeed sorted. Or in other words:

- each access is on the same address as previous:

- or on the next address:

For this, Cairo adds a continuity constraint to its AIR:

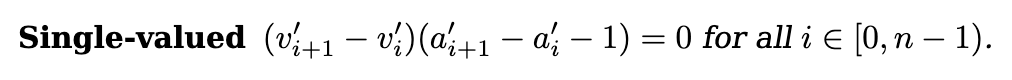

The second thing we want to check is that accesses to the same addresses yield the same values. Now that things are sorted its easy to check this! We just need to check that:

- either the values are the same:

- or the address being accessed was bumped so it’s fine to have different values:

For this, Cairo adds a single-valued constraint to its AIR:

And that’s it! We now have proven that the columns represent correct memory accesses through the whole memory (although we didn’t check that the first access was at address , not sure if Cairo checks that somewhere), and that the accesses are correct.

That is, as long as contains the same list of accesses as .

A multiset check between and

To ensure that two list of elements match, up to some permutation (meaning we don’t care how they were reordered), we can use the same permutation that Plonk uses (except that plonk fixes the permutation).

The check we want to perform is the following:

But we can’t check tuples like that, so let’s get a random value from the verifier and encode tuples as linear combinations:

Now, let’s observe that instead of checking that these two sets match, we can just check that two polynomials have the same roots (where the roots have been encoded to be the elements in our lists):

Which is the same as checking that

Finally, we observe that we can use Schwartz-Zippel to reduce this claim to evaluating the LHS at a random verifier point . If the following is true at the random point then with high probability it is true in general:

The next question to answer is, how do we check this thing in our STARK?

Creating a circuit for the multiset check

Recall that our AIR allows us to write a circuit using successive pairs of rows in the columns of our execution trace.

That is, while we can’t access all the and and and in one shot, we can access them row by row.

So the idea is to write a circuit that produces the previous section’s ratio row by row. To do that, we introduce a new column in our execution trace which will help us keep track of the ratio as we produce it.

This is how you compute that column of the execution trace as the prover.

Note that on the verifier side, as we can’t divide, we will have to create the circuit constraint by moving the denominator to the right-hand side:

There are two additional (boundary) constraints that the verifier needs to impose to ensure that the multiset check is coherent:

- the initial value should be computed correctly ()

- the final value should contain

Importantly, let me note that this new column of the execution trace cannot be created, encoded to a polynomial, committed, and sent to the verifier in the same round as other columns of the execution trace. This is because it makes uses of two verifier challenges and which have to be revealed after the other columns of the execution trace have been sent to the verifier.

Note: a way to understand this article is that the prover is now building the execution trace interactively with the help of the verifier, and parts of the circuits (here a permutation circuit) will need to use these columns of the execution trace that are built at different stages of the proof.

Inserting the public memory in the memory

Now is time to address the second half of the problem we stated earlier:

Second, we haven’t proven that the memory contains fixed values in specific addresses. For example, it should contain the program itself in the first cells.

To do this, the first accesses are replaced with accesses to in . on the other hand uses acceses to the first parts of the memory and retrieves values from the public memory (e.g. ).

This means two things:

- the nominator of will contain in the first iterations (so ). Furthermore, these will not be cancelled by any values in the denominator (as is supposedly using actual accesses to the public memory)

- the denominator of will contain , and these values won’t be canceled by values in the nominator either

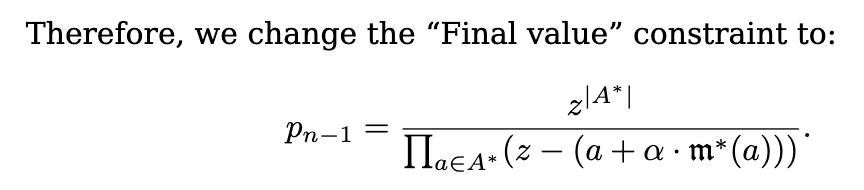

As such, the final value of the accumulator should look like this if the prover followed our directions:

which we can enforce (as the verifier) with a boundary constraint.

Section 9.8 of the Cairo paper writes exactly that: